If you’re an American of European descent, you probably have at least a few immigrant ancestors for whom you’re searching. In this installment of MCDL’s “how to” series, we’ll take a look at the best strategies and resources for learning about these family members. Though this article will mostly focus on researching individuals who arrived in the U.S. during the height of immigration in the early 1900s, it will include resources for locating individuals who arrived here earlier, too.

In general, researching immigrant ancestors is a three-step process. This blog post will discuss each step, then provide an example to illustrate the search process.

Step 1: Start with records in the U.S.A.

Researching immigrants starts like all other research. Collect sources about your ancestor, such as death certificates, obituaries, church records and more. At the top of your priority list, should be the U.S. Federal Census. Last month, Lisa Rienerth wrote an excellent blog post on this topic and noted how the census can help lead to naturalization and immigration records. (See here for details.)

After you’ve exhausted records from the U.S., the next steps involve finding naturalization records and passenger lists. If your ancestor became a U.S. citizen after 1906, I recommend trying to find naturalization records first. Otherwise, Steps 2 and 3 could be conducted simultaneously, or in either order.

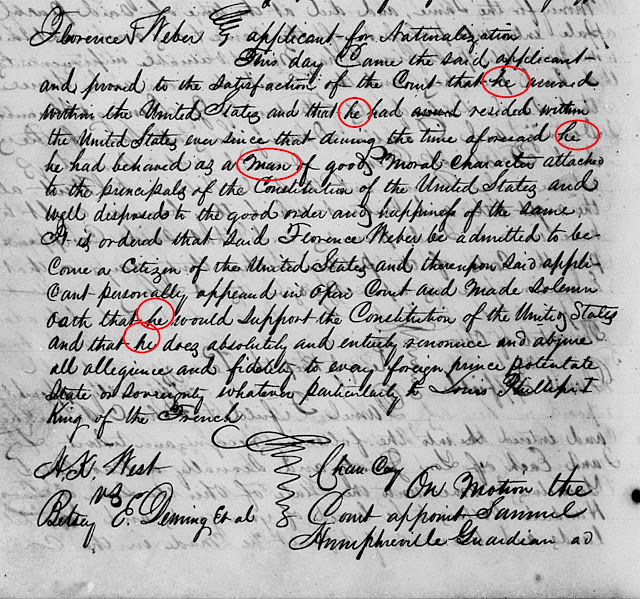

Step 2: Find your ancestor’s naturalization record

Kathy Petras has written two fantastic posts about naturalization records in the past: see Naturalization Records and U.S. Naturalization Records for Women for in-depth information on laws, facts in records, and tips for finding documents (especially if your ancestor was in Medina County).

FamilySearch is a great place to search for naturalization records. If your ancestor became a citizen while living in Ohio, see the list of relevant online collections here. If your ancestor became a citizen in a state other than Ohio, see FamilySearch’s list of all online naturalization records here. Note: Some of these collections are on the subscription database Ancestry, but you can access these for free from MCDL.

Step 3: Find your ancestor’s passenger list

When you search for your ancestor’s passenger list, keep these points in mind:

- The terms Passenger Manifest, Ship Manifest, and Passenger List refer to the same type of record.

- United States passenger lists are all arrivals.

- Few countries document individuals leaving. (Exceptions: limited departure records are available from Germany and England.)

- Date and place affect sources, information, and searching.

|

| MCDL owns many volumes of the Passenger and Immigration Lists Index that can help research immigrants arriving in the USA in the 1800s. |

Before 1820, passenger lists were not required by the U.S. government. However, some were created. Of the early passenger lists that have survived, many have been indexed in Passenger and Immigration Lists Index by P. William Filby. This multi-volume set of books is available in the MCDL collection (currently housed in the 1907 room).

After 1820 (when the U.S. federal government mandated creation of passenger arrival lists), these records have limited details about the voyage and the passengers, including:

After Ellis Island opened in 1892, passenger lists steadily grew to include more details. This timeline summarizes the information you may find in these records:

While the date of the record determines what information it may contain, knowing the place where the record was created impacts locating it. Passenger list records are generally organized by the place (“port of entry”) where the immigrant entered the country.

After 1820 (when the U.S. federal government mandated creation of passenger arrival lists), these records have limited details about the voyage and the passengers, including:

- The captain’s name, the ship’s name, the ports of departure and arrival, and the date.

- The passenger’s name, age, sex, occupation, nationality, and country they intend to inhabit.

- 1893 - details added about a passenger’s marital status, literacy, last residence and final destination, financial status, if they were previously in U.S. or have relatives in U.S., if the individual was a prisoner, poor, or polygamist, and their mental and physical health.

- 1906 - details added about the passenger’s physical description, and place of birth, and if they were an anarchist.

- 1907 -- lists become 2 pages long and include name and address of a living relative in country of origin.

- 1919 - lists add questions about head tax, the purpose of the passenger’s visit, belief in overthrowing government, and if they were previously deported.

- 1925 - the lists add three questions pertaining to immigration visas.

While the date of the record determines what information it may contain, knowing the place where the record was created impacts locating it. Passenger list records are generally organized by the place (“port of entry”) where the immigrant entered the country.

Ellis Island is the most famous port of entry, with more than 12 million immigrants entering the U.S. from this site, while it was in operation between January 1, 1892 and November 12, 1954. Before Ellis Island opened, Castle Garden (aka Castle Clinton or Fort Clinton) served as America's first official immigration center, with 8 to 12 million immigrants entering the country through this earlier port.

To find records for Ellis Island, Castle Garden, and earlier New York arrivals, try the following resources:

- With a free account, search the Ellis Island website for records, including images of passenger lists and ships.

- Search the Castle Garden website for free (no account required), for text-only records on 11 million immigrants from 1820 through 1892.

- Search passenger lists for both Ellis Island and Castle Garden with Ancestry. Search for free at Medina County District Library, using Ancestry’s collection of “New York, Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957.”

- FamilySearch also provides access to information from Ellis Island and Castle Garden. See FamilySearch’s collections of passenger lists and indexes here.

Besides Ellis Island and Castle Garden in New York, other major U.S. ports include Baltimore, Boston, New Orleans, and Philadelphia. To search for records from these ports, try:

FamilySearch

- Baltimore Index and Passenger Lists (1820-1948)

- Boston Index and Passenger Lists (1820-1891)

- New Orleans Passenger Lists (1820-1945)

- Philadelphia Index and Passenger Lists (1800-1882)

Ancestry

Search the Ancestry Card Catalog United States Passenger Lists for the following collections (and many more):

- Baltimore, Passenger and Immigration Lists, 1820-1872

- Boston, 1821-1850 Passenger and Immigration Lists

- Philadelphia, Passenger and Immigration Lists, 1800-1850

- New Orleans, Passenger Lists, 1813-1963

This is a lot of information. Here’s an example of how the process works:

|

| Helyak Family, date/place unknown. Copy in the collection of the author. |

The gentleman on the far right in the photo is my great-grandfather Michael Hellock (born Mihaly Helyak). When I began to research him, I wanted to learn where he had been born, when he arrived in the U.S.A., and when he'd become a naturalized citizen. Since Michael had a typical, twentieth-century immigration experience, he makes an excellent example of the research process and records you can expect to find.

Step 1: Start with records in the U.S.A.

Though I found my great-grandfather’s death certificate, obituary, and social security application, the most helpful source was the U.S. census. I located Michael on the 1910, 1920, 1930, and 1940 censuses. Here is the relevant information from these records:

Name | Age | Birthplace | Immigration Year | Naturalization Status | Language | |

1910 | Michael Helak | 20 | Hungary | 1905 | AL [Alien] | English [?] |

1920 | Mike Hellock | 29 | Austria | 1904 | AL | Slovak |

1930 | Michael Helak | 40 | Czechoslovakia | 1905 | NA [Naturalized] | Slovak |

1940 | Michael Hellock | 51 | Slovakia | - | - | - |

From these records, I learned that Michael became a naturalized citizen between 1920 and 1930, that he arrived in the USA around 1904-1905, and that he came from somewhere around Austria-Hungary-Slovakia. It also gave me options for how his name might be spelled. These clues gave me the information that I needed to begin Step 2.

Step 2: Find your ancestor’s naturalization record

When I originally searched for Michael’s record (about 20 years ago), census records indicated that he had naturalized between 1920 and 1930, while living in Jefferson County, Ohio. I had to go to the county courthouse, look at indexes, and search through bound ledgers of records. Today, his records can be found with a few mouse clicks.

Since Michael spelled his name in a variety of ways, I searched for Helyak, Hellock, and a couple other variations. The first document I found was his “Declaration of Intention” (aka “First Papers”). It includes great personal details, plus specific information on the port through which he entered the country (New York), the ship he came on (Ultonia), and its date of arrival (28 June 1906).

The next document I found was the “Petition for Naturalization.” Be aware that these are at least two pages long, so browse pages around your record, to make sure you don’t miss something! For Michael, a copy of his Declaration was inserted prior to the Petition, making it three pages. While much of the information from the Declaration is repeated, the Petition also includes info on Michael’s children.

Step 3: Find your ancestor’s passenger list

With information from the census records and the naturalization records, I next looked for a passenger list with Michael on it. For Michael, his naturalization record specified that he arrived on 28 June 1906 in New York aboard the Ultonia.

I searched FamilySearch’s “New York Passenger Arrival Lists (Ellis Island), 1892-1924” collection because it was the place I needed, for the right time period, and it’s a free resource. In searching it, I found not one, but two records for Michael. He first arrived on 21 May 1904... and then he arrived again on 24 June 1906 -- almost the exact date in his naturalization records!

Be sure to read all of the details on the passenger lists. For Michael’s 1906 record, this includes his last residence (Zahar, today Zahor, Slovakia), his destination in the U.S. (Bridgeport, PA), and the name of a relative/friend he will be meeting in the U.S. (his brother, Gyorgy Helyak). These facts confirm information from the naturalization record, plus add a new relative, Gyorgy, to my family tree. This illustrates another important point of researching immigrant ancestors -- the idea of chain migration. In the early 1900s, it was common for one relative to come to the United States, then provide aid to have other family members join them. For Michael and Gyorgy, their three siblings also came to the U.S., but only one sister stayed permanently.

Though my questions about Michael’s experience with immigration and naturalization have been answered, the clue about Michael’s brother Gyorgy means the search process can begin all over again!

Some Final Tips for Searching

If you’re having trouble finding your ancestor...

With information from the census records and the naturalization records, I next looked for a passenger list with Michael on it. For Michael, his naturalization record specified that he arrived on 28 June 1906 in New York aboard the Ultonia.

I searched FamilySearch’s “New York Passenger Arrival Lists (Ellis Island), 1892-1924” collection because it was the place I needed, for the right time period, and it’s a free resource. In searching it, I found not one, but two records for Michael. He first arrived on 21 May 1904... and then he arrived again on 24 June 1906 -- almost the exact date in his naturalization records!

| |

|

Arriving in the United States more than once was not uncommon in the 1900s. With technological improvements, in the early 1900s a trip from Europe to America could take as little as two weeks. With shorter travel times, individuals would come to the U.S. for work, save money, then return to the “old country.” They would then return to the U.S. for work, and the cycle could repeat itself -- or the individuals might decide to stay and become citizens. These individuals (including Michael) are called “birds of passage.” (Learn more here.)

Be sure to read all of the details on the passenger lists. For Michael’s 1906 record, this includes his last residence (Zahar, today Zahor, Slovakia), his destination in the U.S. (Bridgeport, PA), and the name of a relative/friend he will be meeting in the U.S. (his brother, Gyorgy Helyak). These facts confirm information from the naturalization record, plus add a new relative, Gyorgy, to my family tree. This illustrates another important point of researching immigrant ancestors -- the idea of chain migration. In the early 1900s, it was common for one relative to come to the United States, then provide aid to have other family members join them. For Michael and Gyorgy, their three siblings also came to the U.S., but only one sister stayed permanently.

Though my questions about Michael’s experience with immigration and naturalization have been answered, the clue about Michael’s brother Gyorgy means the search process can begin all over again!

Some Final Tips for Searching

If you’re having trouble finding your ancestor...

- Try searching variant spelling of your ancestor’s surname.

- Spell a surname with wildcard characters. In most databases you can use a ? to represent a single letter in a name, while a * can represent multiple letters in a surname. (Example: searching for Sm?th will find records for Smith or Smyth, while searching for Smith* will find results for Smith or Smithe or Smithson.)

- Learn the ethnic name equivalents and try searches in the immigrant’s native language. While it’s a myth that immigration officials changed your family’s name at Ellis Island (learn more here), you ancestor may not have used the English version of his or her given name. Their surname may also have ethnic variants.

- Learn about pronunciation in your immigrant ancestor’s native language. In some cases clerks may have recorded the name as they heard it.

- Remember: Not everything is online and not all records have been indexed. Check back periodically, or consider which repository might hold a copy of your ancestor’s documents.

- Try searching for relatives of your ancestor -- siblings, spouses, children, etc.